Constructing the database: creation, inspiration and compromise in suffrage research

When, as a researcher, I was asked to take part in the Historical Association’s new Women’s Suffrage Resources project for schools, and to populate the database for it, I jumped at the chance. Who wouldn’t? I was presented with an opportunity to delve into the archives, reaching back in time to the symbolic beginnings of the organised women’s suffrage movement in 1866 when almost 1,500 women signed a petition for female suffrage, presented to Parliament by Liberal MP John Stuart Mill, and to work right through to government records listing suffragettes arrested between 1906 and 1914, over 40 years later.

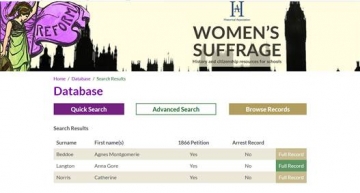

My initial task was to populate the database with the names and details of as many suffrage campaigners as possible from these documents and another, titled the ‘Declaration in Favour of Women’s Suffrage’, dated 1889. Chronologically, the 1889 Declaration, formulated by the Central Committee for Women’s Suffrage, sat at a midway point in the pre-war suffrage campaign between the signing of the 1866 petition and the militancy and arrests associated with the later ‘suffragette’ movement. Building a schools’ database from these historical materials was a fresh, exciting approach, as working with such sources inevitably reveals less well-known and often hidden voices from the suffrage past. However, using the selected materials for the database presented several challenges, from both a practical and a historical point of view. The following paper discusses just some of these challenges, how they were negotiated and what compromises were made, exploring the tensions and complications that shaped whose and which inspirational suffrage stories the project tells so far.

The suffrage database proposal for schools was ambitious. The three documents that had been chosen as sources – the 1866 Women’s Suffrage Petition, the 1889 Declaration and the Suffragettes Arrested Index – together represented around 5,000 people.[i] Names listed on the 1866 petition had already been transcribed and made available online by the parliamentary archives team at Westminster, giving the database a head start. However, many more suffrage campaigner names needed to be transcribed and researched to create a variety of datasets, including birth and death years, birth towns and countries, occupations and suffrage society membership, as well as exploring other political interests they may have had outside the women’s suffrage movement. The database now shows that numerous signatories to the 1866 petition were active in earlier anti-slavery and woman-centred campaigns, like the Repeal of Contagious Diseases Acts led by signatory Josephine Butler, and how some later suffragettes were also trade unionists, like Emma Sproson, or sought political office as MPs or Councillors after the First World War, like Dora Montefiore.

The time constraints for researching the database were challenging, set at approximately 80 days. Therefore, the number of suffrage campaigners included in the database had to be reduced to ensure that it was populated as richly as possible. Historical research is immensely rewarding but can be a complex and lengthy process. Researching suffrage campaigners means pulling together a wide variety of information sources, from primary materials such as census, birth and death records, to identifying existing work by other historians, whether in print or online. So, after some debate, a compromise was reached, and the 1889 Declaration was set aside. There were several reasons for this. It felt vitally important to the team to ensure that the female pioneers who signed the 1866 women’s suffrage petition were recognised on the database. After all, their actions symbolised the beginnings of the nationally organised ‘votes for women’ movement, and this earlier period is often underrepresented in the teaching of suffrage histories. Equally, the years of suffragette militancy in the early twentieth century represented a pivotal moment for the campaign, both popularly and politically. Suffrage histories widely acknowledge that suffragette ‘antics’, initiated by members of Mrs Emmeline Pankhurst’s WSPU, reinvigorated a tired yet persistent women’s suffrage movement, popularising its politics – at least to begin with – by grabbing newspaper headlines, and seeing an increase in membership across all suffrage societies, including the law-abiding NUWSS, formed in 1897 and led by Mrs Millicent Fawcett.

Together, these sources span the duration of the organised women’s suffrage campaign before the War, and before the vote was given to those women deemed qualified under the Representation of the People Act passed in 1918. Therefore, building the database around them allows pupils and teachers room to explore how suffrage campaigning changed during those years, the reasons why and whether the social class, composition and diversity of those that campaigned for the vote changed too. For instance, the inclusion of the Suffragettes Arrested Index, compiled in the early twentieth century, enabled men to feature in a way that neither the 1866 petition nor the set-aside 1889 Declaration would have allowed. Men had always been involved in supporting as well as opposing the women’s suffrage movement, including many high-profile politicians in the nineteenth century, such as John Stuart Mill. However, it was in the twentieth century that men become more broadly visible in the campaign, forming their own organisations, with some, through militant action, becoming ‘suffragettes in trousers’.[ii]

The vast numbers of women and men committed to law-abiding women’s suffrage societies active in the early twentieth century, notably the NUWSS, are currently underrepresented on the database. However, the overall project looks to address this by producing additional resources, including forthcoming case studies about some of the most interesting and influential women not captured by the database, such as the working-class organiser for the campaign in the north of England, Selina Cooper. Nevertheless, exploring pioneering ‘suffragists’ who signed the 1866 women’s suffrage petition on the database reveals the antecedents of the later suffragist and suffragette societies, and numerous other connections between campaigners across the movement and across the years, often evident through family ties. For instance, the leader of the NUWSS, Millicent Fawcett, was born Millicent Garrett, and though she was considered too young aged 19 years to sign the 1866 petition, several of her family members did so. These included her elder sister Elizabeth Garrett, who went on to become Dr Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, the first female doctor in Britain. Remaining active in the suffrage campaign, Garrett Anderson went on to join the law-abiding NUWSS, led by her sister Millicent, but in 1908 left to join the ‘suffragette’ WSPU, aged 72 years. Through campaigners like Garrett Anderson and many others, suffrage histories seek to challenge the sharp divisions often portrayed between suffragists and suffragettes, because the reality was always more complex. The database shows that the 1866 petition was signed by early tax resistors, such as Charlotte Babb and sisters Anna and Mary Priestman, who, in evading taxes, were breaking the law and flouting arrest long before the term ‘suffragette’ came into being. It also demonstrates, on the other hand, how some suffragettes like Adelaide Knight quickly turned from WSPU militancy during the campaign to more peaceful and progressive politics associated with local working-class, socialist and pacifist movements.

The decision to reduce the overall number of suffrage campaigners on the database also gave the team room to rethink the depth of information that the database could offer to pupils and teachers about suffrage campaigners. Perhaps the most fascinating thing about all histories is the connections we make with people from the past, who may have been just like us or our families. Therefore, the research was expanded to create as many short biographies as time would allow for the database, centred on campaigners’ suffrage and other activities, and also to identify a variety of weblinks, giving pupils free access to additional materials and resources via the database, such as campaigner photographs, letters, prison diaries and suffrage scrapbooks. This enables the database to provide a richer, fuller sense of suffrage lives – who were ‘votes for women’ campaigners and what did they look like? What did they do during the campaign? Were they or their families rich or poor? Why might they have signed the petition in 1866, or become suffragettes in the twentieth century? And how were they treated?

There is often a plethora of information to be found about some suffrage campaigners, yet very little – or nothing at all – to find about others. For example, some signatories on the 1866 women’s suffrage petition are well known in suffrage histories. A significant number of these haled from radical liberal families with reputations for supporting social and political reform movements, such as the Brights and the McLarens. Or else they were extraordinary individual women of their time, like Scottish astronomer and scientist Mary Somerville and writer and sociologist Harriet Martineau. Many were middle or upper class and so possessed the time and resources to write letters and books, keep diaries and have portraits or photographs taken (photography was then in its infancy), and they were often mindful of preserving family reminiscences as legacies, leaving a rich trail for historians to follow. However, many more led very ordinary lives, were labouring or working class, had popular or ‘common’ names, may not have been involved in suffrage campaigning beyond signing the 1866 petition, and left few materials or discernible details to trace them by with any certainty. Many documents that might provide information about their birth dates, towns and lives, such as census forms, required minimal details in this earlier period. They were also filled in by male officials, or by husbands deemed ‘heads of household’ where women were married. Therefore, women’s occupations – sometimes even their names and ages – weren’t always properly recorded. For this reason, and where known, the database lists husbands’ or parents’ occupations, to indicate for pupils what the women’s socio-economic backgrounds and circumstances might have been. Importantly, many women who signed the 1866 suffrage petition recorded where they signed it, and this is often invaluable in tracing their identities. The details vary enormously, from specific addresses that still exist today to simply towns or counties. These details have been added to and recorded for the database, allowing pupils to explore in what streets, towns and regions across Britain pioneering women suffragists were living when they signed the petition, with some even signing abroad, like Mary Somerville in La Spezia, Italy. By drawing this information together with ongoing work by experts Elizabeth Crawford and Dr Anne Dingsdale on the petition, the database gives fresh glimpses into the extraordinary and ordinary lives of often invisible suffragists like Maria Mondy and Lucy Castle, who worked hard from impoverished backgrounds to become teachers by the time they signed the petition, or printer’s wife Susanna Gee, whose local efforts to collect signatures for the petition impacted on the number of supporters recorded in her home town of Denbigh in Wales.

Researching suffragette names listed in the Suffragettes Arrested Index for the database presented different challenges. The better documentation of people’s lives by the state in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries enabled more suffragette birth and death dates, birth towns and regions to be traced than for earlier suffragists on the database. Women were becoming more visible in other ways too – living differently and more independently outside marriage or family ties, with middle-class as well as working-class women increasingly seeking employment outside the home. Suffragette occupations included teachers and typists, shop clerks and journalists, doctors and dancers. There was also an explosion of popular print, photography and local and national newspapers in this period, including suffrage society newspapers. The law-abiding NUWSS had The Common Cause while the militant WSPU had Votes for Women and, later, the Suffragette, and the Women’s Freedom League (WFL) had The Vote newspaper. Together with suffrage historians’ work on this tumultuous time in women’s history, these papers helped to identify suffragettes and inspiring tales of protests, arrests and imprisonments, hunger strikes and forcible feedings for the database, by both women and men, such as actress Kitty Marion and labourer William Ball.

However, using data contained within the index about suffragette arrests raised different queries and challenges for the database. Suffragette names are handwritten in the index, and below each name is a list of the dates and locations where suffragettes were arrested – Bow Street in London, or just in Birmingham, for example. This raised the idea of creating a common dataset between the earlier and later database sources – recording where ‘suffragettes’ were arrested, in line with data showing where suffragists had signed the 1866 suffrage petition. This notion was appealing from a suffrage geographies point of view, but problematic both practically and historically. Suffragettes were often arrested in London yet travelled there from across the country to commit militants acts or take part in demonstrations in and around politically symbolic places like the Houses of Parliament. Simply listing locations for suffragette arrests may have unfairly reinforced the mistaken perception that the suffrage movement was ‘London’-based rather than nationwide. Identifying and recording the home addresses of suffragettes at the time of their arrest was put forward as an alternative suggestion but was also discounted. This too was problematic for the database, not least because the index spans arrests over an eight-year period, between 1906 and 1914. Suffragettes often led nomadic lives during this time, whether travelling the country organising, speaking or committing militant acts, or evading arrest or recapture after temporary release from prison under the ‘Cat and Mouse Act’. However, there is much for pupils to identify with through suffragette roots in their home towns, such as Annie Kenney’s in Saddleworth, Lancashire, or Emily Wilding Davison’s in Blackheath, London (Middlesex).

Collating arrest entries from the index to calculate the number of times each suffragette was arrested for the database also presented challenges. There were some obvious discrepancies between the number of times that historians know some suffragettes were arrested and entries in the index. Suffragette Alice Hawkins, for example, was arrested five times but the index only records three. Was this human error or something else? Suffragette names are often written more than once in the index, and out of its general alphabetical order. Were these simply missed arrest entries, later added into the handwritten book? Or accidental duplications? Some entries cite places like Bow Street, where there were police stations, but sometimes law courts too. Did this mean that every entry was an arrest, or could suffragettes’ subsequent court appearances have also been included on occasion? All of these factors could potentially inflate the true number of times that suffragettes were arrested. Some of these questions were posed to Vicki Iglikowski at the National Archives, who explained that archivists know surprisingly little about the content of the index held there, as its creators left few clues about the boundaries of the information it contains. This means that, for now at least, not all of the questions raised around this fascinating document can be answered. So, to simplify the arrest index for the database, suffragette names where repeated were counted as additions rather than duplications, and entries for each suffragette were assumed to be arrests, and added together to give the total number of times that each was arrested. Suffragette arrests ranged from one to a staggering 14 times, for suffragette Elizabeth Bell, and pupils can now explore this data together with other details on the database about suffragette treatment in prison. But suffragettes also used ‘aliases’ or fictitious names, sometimes to confuse or evade the police, creating another challenge for record-keepers and historians alike. Several suffragette aliases were known to police and are noted in the arrest index; others have since been identified by historians but many more remain undiscovered. Suffragette entries under known aliases for the database have not been merged with entries under their real names but left as they were, recorded separately in the index. This ensures that this fascinating aspect of suffragette tactics is preserved for pupils to explore and, with the help of a project guide to some suffragette aliases, discover what may have been their real number of arrests.

Creating the database for schools, alongside case studies for the project, has been a fascinating research journey. The database now contains over 2,500 names of pioneering suffragists and later suffragettes, with information about their lives and links to additional photographs and other materials where possible. There will always be more about suffrage campaigners to add – the research process is seldom ‘finished’ – but through these lives, the database captures the diversity of the classes, origins, occupations, abilities and genders of people caught up across the years in what became a global women’s suffrage movement. Suffragists and suffragettes range from cotton winders and factory workers, like Elizabeth Bucknall and Minnie Baldock, to aristocrats, like Viscountess Katherine Amberley and Princess Sophia Duleep Singh; they come from all corners of the world, such as anti-slavery campaigner Sarah Parker Remond from America, and suffragette Muriel Matters from Australia; and they involved groundbreaking Victorian women, like Elizabeth Wolstenholme-Elmy, and young radical Edwardian men, like ‘suffragette’ Victor Duval, and many more for teachers and pupils to discover and explore.

[i] Thank you to Dr Mari Takayanagi at the Parliamentary Archives, Stephen Ridgden at Findmypast and Vicky Iglikowski at the National Archives for help and conversations around these documents.

[ii] Quote by Israel Zangwill. See: https://www.parliament.uk/about/living-heritage/transformingsociety/electionsvoting/womenvote/case-studies-women-parliament/suffragettes-in-trousers/suffragettes-in-trousers/