Parliament and the Suffrage Movement

The full resource is FREE to all registered users of the website

If you are not already registered you can sign up for FREE website access to download the full resource.

The problem facing all the campaigns for women’s suffrage was that they couldn’t make the all-male members of Parliament give them the vote; they had to persuade them that it was the right thing to do.

1. Contemporary attitudes towards women

One fundamental difficulty that the campaigners had to overcome was the view of the nature, and therefore the role, of women widely held in Britain, including by its MPs. Not all men held these views, of course, and certainly not all MPs. Further, these views changed a great deal through the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Nevertheless, overcoming these prejudices was an obstacle that all suffrage campaigns had to overcome throughout their task of persuasion.

'Separate spheres': Victorian views on women

- Men and women have different qualities and characters and so take different roles in life: they occupy different worlds. A man’s role is to be out in the world, in business or politics. A woman’s role is to build a home, to care for her husband and children.

- This separation of roles suits the nature of men – rational, active, decisive – and women – emotional, hesitant, indecisive, and so unable to take part in government.

- If women take roles in the world outside the home, families will be neglected.

- Women are not called upon to fight for their country, so have not earned the right to take part in its government.

- A woman’s views will be represented by the man in her household, who has the vote.

- Most women are not interested in politics and don’t care whether they have the vote or not. Suffrage campaigners are a tiny, unrepresentative, middle-class minority.

2. The right to vote

Not all men could vote in parliamentary elections before 1918. The right to vote – the franchise – was based on your wealth, judged by the value of your property.

The franchise changed three times in the nineteenth century, gradually widening it to include more male voters:

- 1832 Reform Act. The franchise had not been changed for centuries before this date and varied a great deal from place to place. This Act established different kinds of franchise in boroughs (places, mainly towns, that had been given the right to elect MPs by a Royal Charter) and rural areas (counties) and extended the right to vote from about 8% of all men to just under 20%. In fact, the Act made things worse for women by specifying that voters had to be male, rather than, as before, a (propertied) person, through which a very few women had been able to vote previously.

- 1867 Reform Act. Extended the franchise to include all men in boroughs who owned or rented property worth £10 a year. As a result, just under 30% of all men had the vote.

- 1884 Reform Act. Extended the same franchise, owning or renting property worth £10 a year, to the rest of the male population. About 60% of the men now had the vote.

To put it another way – just over 100 years ago, four British men in ten did not have the right to vote. This presented a problem of tactics to campaigners for women’s suffrage. Should they demand the vote for women on the same basis as men at that time? Or campaign for the vote for all adults, men and women?

3. Petitions and private member’s bills

One way of making Parliament consider public opinion is to submit a petition, signed by as many people as possible, to indicate to MPs the level of concern. The Kensington Society petition, with 1,521 signatures calling for votes for women, was submitted in 1866. MP John Stuart Mill presented it to Parliament and, during the debate on the 1867 Reform Act, proposed an amendment that replaced the word ‘man’ with ‘person’. His proposal was defeated by 196 votes to 73. Disappointment at this defeat led to the formation of the London National Society for Women’s Suffrage, but it also showed that quite a number of MPs were sympathetic.

The NUWSS continued to petition Parliament as part of their campaigns – almost 17,000 petitions were submitted over the next 50 years. One, in 1896, contained 260,000 signatures.

These were often supported by private member’s bills. Any MP can put forward a ‘bill’ – a proposal for a new law. They are called private member’s bills because they are proposed by an individual MP, not by the government. Almost every year from 1867, an MP proposed a private member’s bill giving the vote to women and, on three occasions, the bill won a majority (Pugh, The March of the Women).

Parliament makes or changes the law through a lengthy and careful process. A bill is given a brief ‘first reading’. Time is then set aside for a ‘second reading’ and a full debate, followed by a ‘committee stage’ in which a smaller group of MPs examine the bill in detail and make any changes. The bill then has to be agreed by the House of Lords, as well as the House of Commons, in a ‘third reading’, before being approved by the monarch and so becoming an act – a new law. All this business takes time and organisation, which is controlled by the government and its ministers. Only with their support can a private member’s bill move on to become an act. Governments throughout this period were not prepared to give their support to private member’s bills in favour of votes for women (see 5 below).

4. Women and local democracy

A number of changes in the law in the 40 years after the Second Reform Act considerably improved women’s democratic rights.

- 1869 Municipal Franchise Act. Women ratepayers could vote in local elections in towns and cities.

- 1870 Education Act. School Boards were set up to run schools. Women ratepayers could both vote for and stand as members of these Boards.

- 1875 Public Health Act. Women ratepayers had been able to vote for Poor Law Guardians since 1835, but now they could stand for election themselves.

- 1882 Married Women’s Property Act. Married women could control and own property in their own right. This built on the 1870 Act, which allowed a married woman to keep her own earnings and inherit property. (Before this Act, everything a woman owned became her husband’s property when she married. It therefore increased the number of women who now met the property qualification for the franchise.)

- 1888 County Council Act. Women ratepayers could now vote in local county and borough council elections.

- 1907 Qualification of Women Act. Women could stand for election as members of local county and city councils.

The extensions of the franchise in 1867 and 1884 had a profound effect on political parties. With an electorate of several million, and voting in secret from 1872, parties had to be better organised. Both parties recruited women to help: the Conservative Party founded the Primrose League in 1883, in which women were heavily involved, and the Liberals formed the Women’s Liberal Federation in 1886. Thousands of women joined one or other of these. Women were also active in trade unions and in the rise of the Labour Party.

All these changes disproved many of the prejudices listed above. By the beginning of the twentieth century, however, one huge block remained to women’s right to take a full part in the democratic process of running the country: the right to vote and stand in elections to Parliament.

5. Political parties

All the main political parties were split over the issue of women’s suffrage.

- The Conservatives were in government for most of the years from 1885 to 1906. Some Conservatives could see that giving the vote to women on the same basis as men (a property franchise, see 2) would give the vote to middle- and upper-class women, who would be more likely to vote for them. Conservative leaders Benjamin Disraeli, the Marquess of Salisbury and Arthur Balfour were sympathetic to the women’s cause. However, others, particularly the large Conservative majority in the House of Lords, were completely against changing the status of women. Conservative leaders knew that they could never get the House of Lords to pass a bill for women’s suffrage. A leading Conservative, Lord Curzon, was president of an organisation called the League for Opposing Women’s Suffrage.

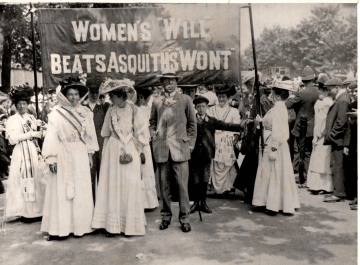

- The Liberals were in power from 1905 to 1922 (they had been in power at points in the nineteenth century, under William Gladstone and others). Many Liberals supported women’s suffrage, including leading Liberals like David Lloyd George. However, their party leader (and prime minister from 1908 to 1916) was Henry Asquith, who opposed votes for women. He feared that giving the vote to women on the basis of a property franchise would only produce more Conservative voters, but also firmly opposed women’s equality.

- The Labour Party was set up to represent trade unions and the working class, winning 29 seats in the 1906 election, rising to 42 in 1910. The Labour Party were also split initially. Many simply wanted to campaign for votes for all men, opposing the property franchise that excluded most working men. They argued that adding on votes for all women as well would weaken their cause and make it even more unlikely to be achieved. However, many in the Labour Party consistently supported votes for women, including the first leader, Keir Hardie. Hardie was close to the Pankhursts and lived for some time with Sylvia Pankhurst. However, the Party objected to the WSPU’s support for the vote for women on the same basis as men, which excluded most working men. Full adult suffrage, for all men and women, became Labour Party policy in 1912 and gained the support of the NUWSS.

- The Irish Parliamentary Party wanted Home Rule – independence – for Ireland. They were also divided on the issue of women’s suffrage.

6. The crisis of 1910–12

Votes for women was just one of the issues that the Liberal government was trying to deal with – and not, for many of them, the most important. In addition to finding the money for the arms race with Germany to build battleships, and Irish Home Rule, they had a big social agenda, wanting to bring in sickness and unemployment benefits for workers, paid for by raising taxes. Opposition to these plans led to two general elections in 1910 as the Liberals called for public support, in which they lost seats, becoming dependent on the support of Labour and Irish MPs to continue.

In 1910, under pressure from both the NUWSS and the WSPU, a joint committee of MPs from all parties drew up a Conciliation Bill. The suffragettes called a halt to their protests while these talks were going on. The Bill proposed to give the vote to women on the same basis as men and was passed as a private member’s bill. Asquith refused to give it government time, leading to the violent suffragette demonstration in November in which many women were assaulted by the police.

The second Conciliation Bill was passed in 1911 with the same terms. Liberal leaders opposed it from two sides: Lloyd George because it left out thousands of working women, and Asquith because it would hand votes to the Conservatives. Asquith then proposed a government bill to give the vote to all men, hinting that it could perhaps be amended to include all women as well. Not only did he know full well that such a bill would never get through Parliament, but the Speaker announced that such an amendment would not be allowed as it was not amending but completely changing it.

The suffragette reaction was to step up their campaign of violence and arson. In 1912, the third Conciliation Bill was defeated, partly in reaction to the suffragettes’ campaign, but also because the Irish voted against it as they wanted government time to be given to their Home Rule Bill.

7. The Representation of the People Act 1918

In 1916, the government began to plan for the next general election after the war and set up an all-party conference, chaired by the neutral Speaker of the House of Commons. It was immediately obvious that the war had changed everything.

- Before the war, voters had to prove that they had lived in the same place for a year. During the war, millions of people had been on the move, to fight and to work. Most men in the armed forces in 1916 were not even in Britain.

- Many of the 40% of men excluded from voting under the old property qualification had shown their readiness to fight and die for their country. They could obviously no longer be excluded from full adult male suffrage.

- Women had clearly made a huge contribution to the war effort as well. The proportion of women in employment rose from 24% to 37% from 1914 to 1918, and their work in munitions factories, farming and transport had been particularly significant. Even a die-hard opponent of women’s suffrage like Asquith was forced to admit, ‘How could we have carried on the war without them?’ Those MPs who had previously resisted women’s suffrage because they did not want to be seen to be giving way to the violence of the suffragettes now had a reason to change their minds.

Yet some of the old prejudices remained. If there was full adult suffrage for both sexes, women voters would outnumber men. Young women were believed to be too impressionable to use their vote sensibly. The Representation of the People Act 1918 therefore gave the vote to nearly all men over 21 and women over 30 who paid local taxes or were married to someone who did. As a result, 12.5 million men (an increase of 4.5 million) and 8.5 million women had the right to vote. Women could also stand for election as an MP.

The young women denied the vote were just the age group who had done the most war work. This anomaly was put right in 1928, when women gained the right to vote at 21 on the same terms as men.